Past, Present, Perfect Tense

Past, Present, Perfect Tense

Date

2019

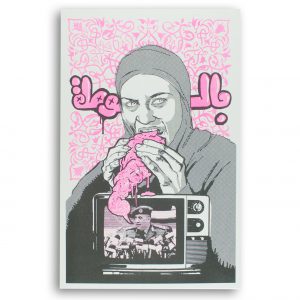

Media

Silkscreen

Format

Artist Book

Dimensions

14 × 11.25 × 0.75 in

Location

St. Augustine, FL

Edition size

11

Binding

Handsewn

Collection

Collection Development, Limited Edition Artists Books$ 2,400.00

Unavailable

View Collectors

Columbia University, Butler Library

Emory University

University of Central Florida (UCF)

University of Florida

University of Miami

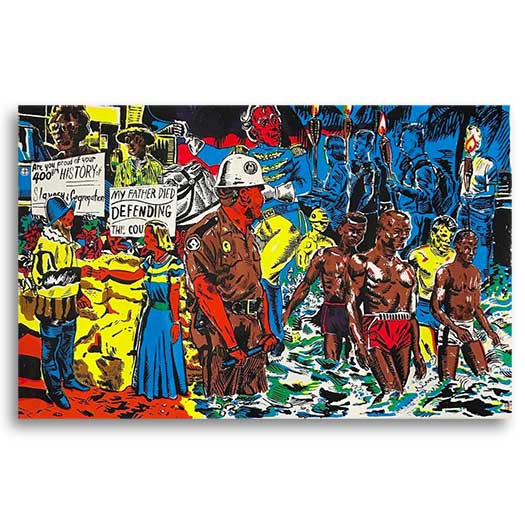

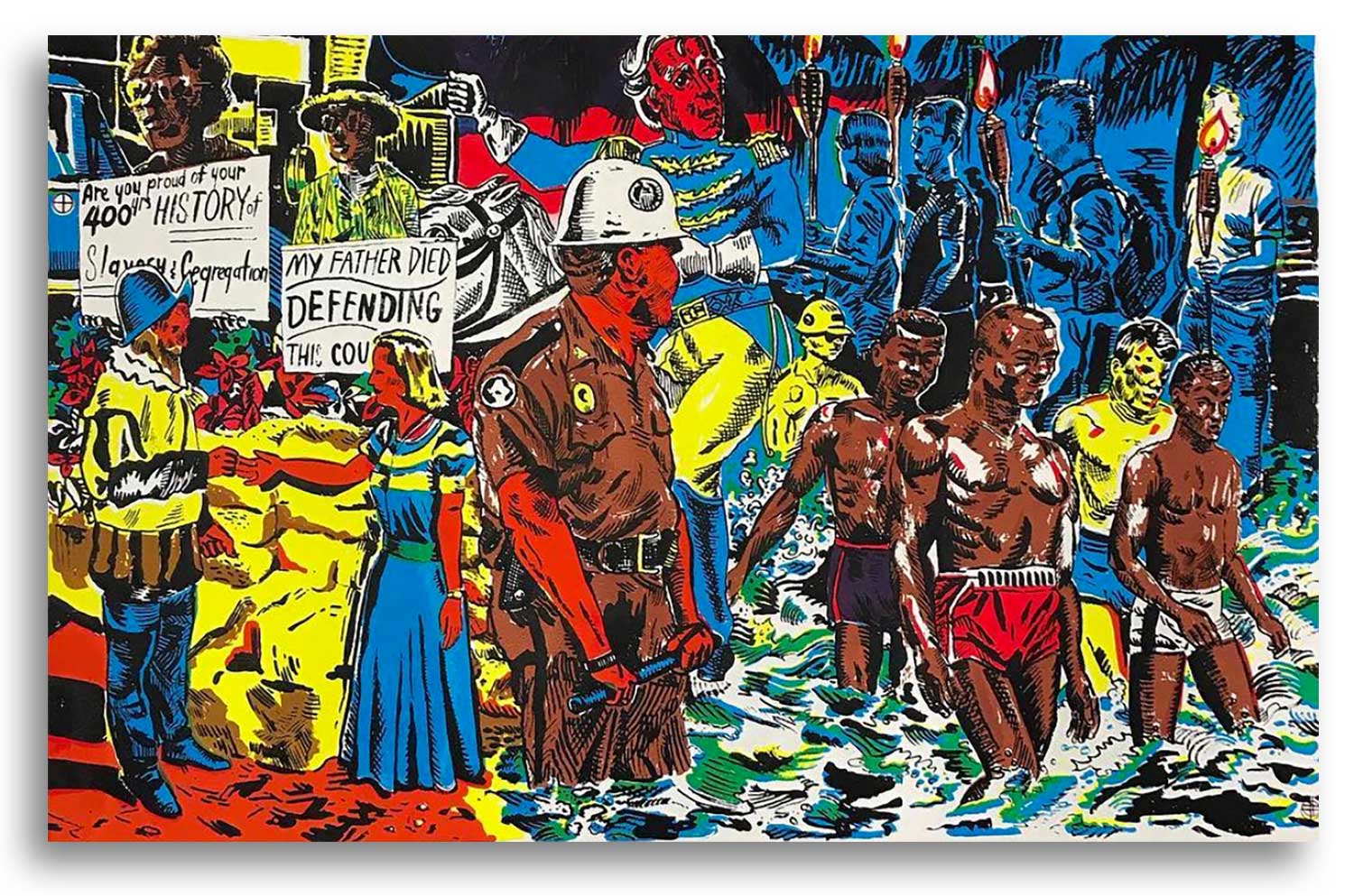

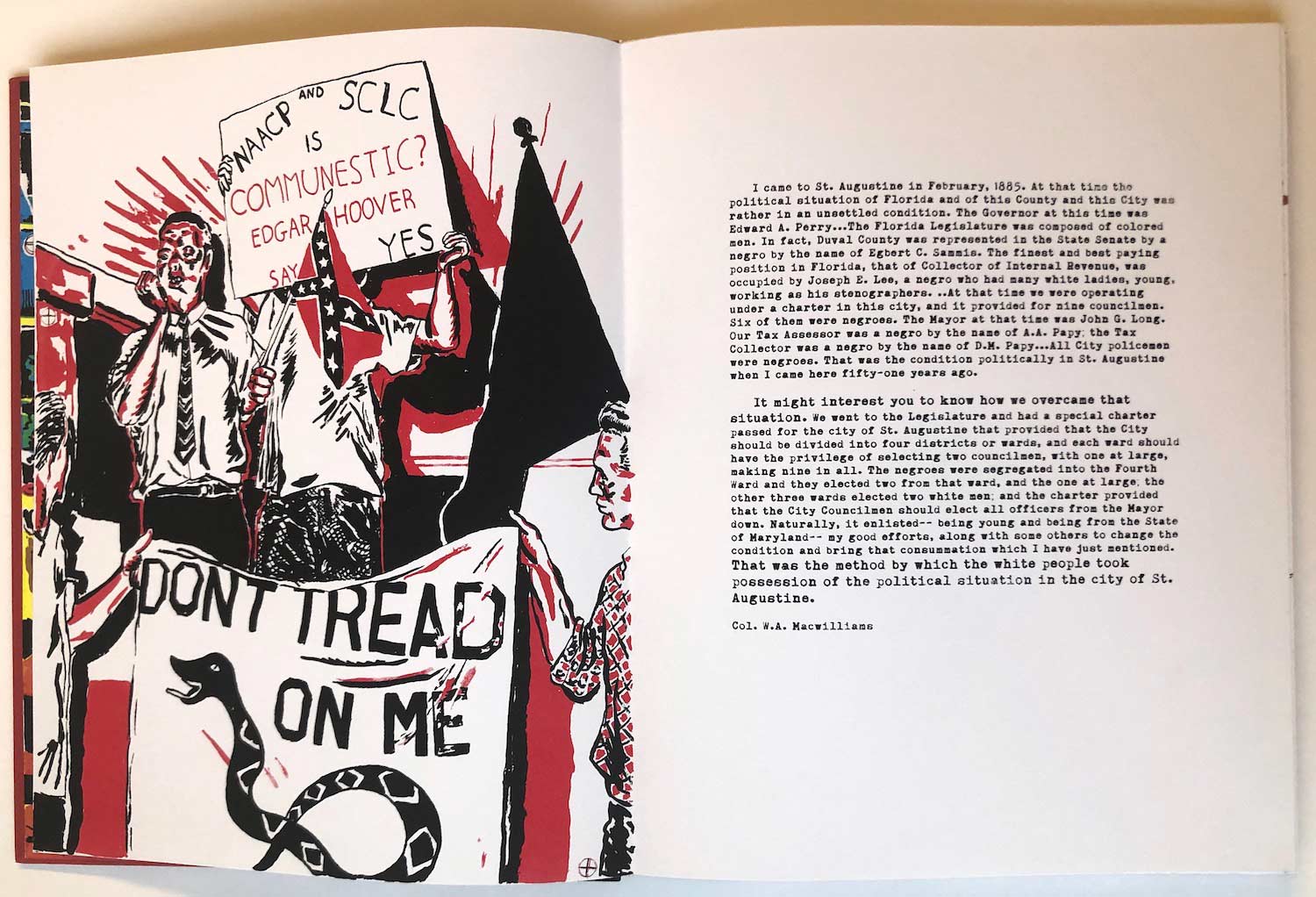

Through extensive research at the ACCORD Civil Rights Museum in St. Augustine Florida, where the artist now resides, Taylor constructs a narrative of events between 1960 and 1964 chronicling the Civil Rights struggles of St. Augustine’s residents and the city’s resistance to racial integration. The artist reanimates these occurrences through a combination of forthright text and brash imagery. Taylor’s iconic illustrative style comprises complex and layered brushwork. The contrasting colors and overlapping imagery of the multilayered screen prints add to the chaos of the events and the struggles faced by the Civil Rights movement in St. Augustine and throughout the country. As the title implies, elements from this historical narrative continue to seep into the present day, may this edition be used as a teaching tool to guide educators, activists and advocates.

From the artist:

In the grammatical sense, the Present Perfect Progressive Tense refers to an action that has begun in the past, continues into the present, and possibly into the future. As such, the events of the Civil Rights Movement in St. Augustine, Florida are as much a part of the city today as they were in 1964.

Trading solely on its identity as the oldest European settlement in the U.S., the town was readying itself to celebrate its 400th anniversary in 1965. Local activists from the NAACP contacted president Kennedy to ask that he withhold considerable federal funding for what was to be a segregated celebration. The events that followed caused Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. to call the city the most lawless he had ever visited. This book examines a city’s, and by extension, a nation’s, unresolved debt.

—Mike Taylor, March 2019

Text from the book:

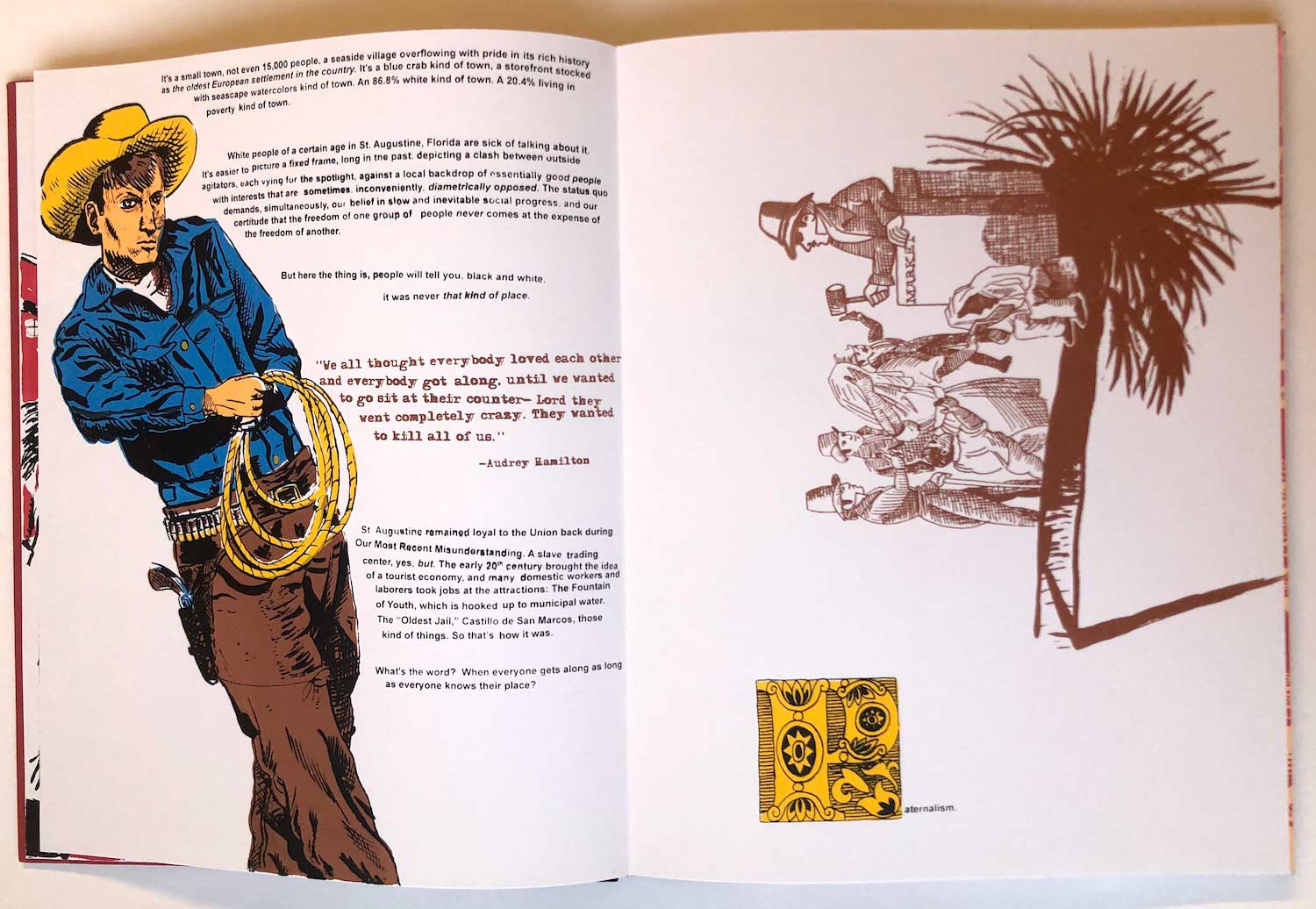

It’s a small town, not even 15,000 people, a seaside village overflowing with pride in its rich history as the oldest European settlement in the country. It’s a blue crab kind of town, a storefront stocked with seascape watercolors kind of town. An 86.8% white kind of town. A 20.4% living in poverty kind of town.

White people of a certain age in St. Augustine, Florida are sick of talking about it. It’s easier to picture a fixed frame, long in the past, depicting a clash between outside agitators, each vying for the spotlight, against a local backdrop of essentially good people with interests that are sometimes, inconveniently, diametrically opposed. The status quo demands, simultaneously, our belief in slow and inevitable social progress, and our certitude that the freedom of one group of people never comes at the expense of the freedom of another.

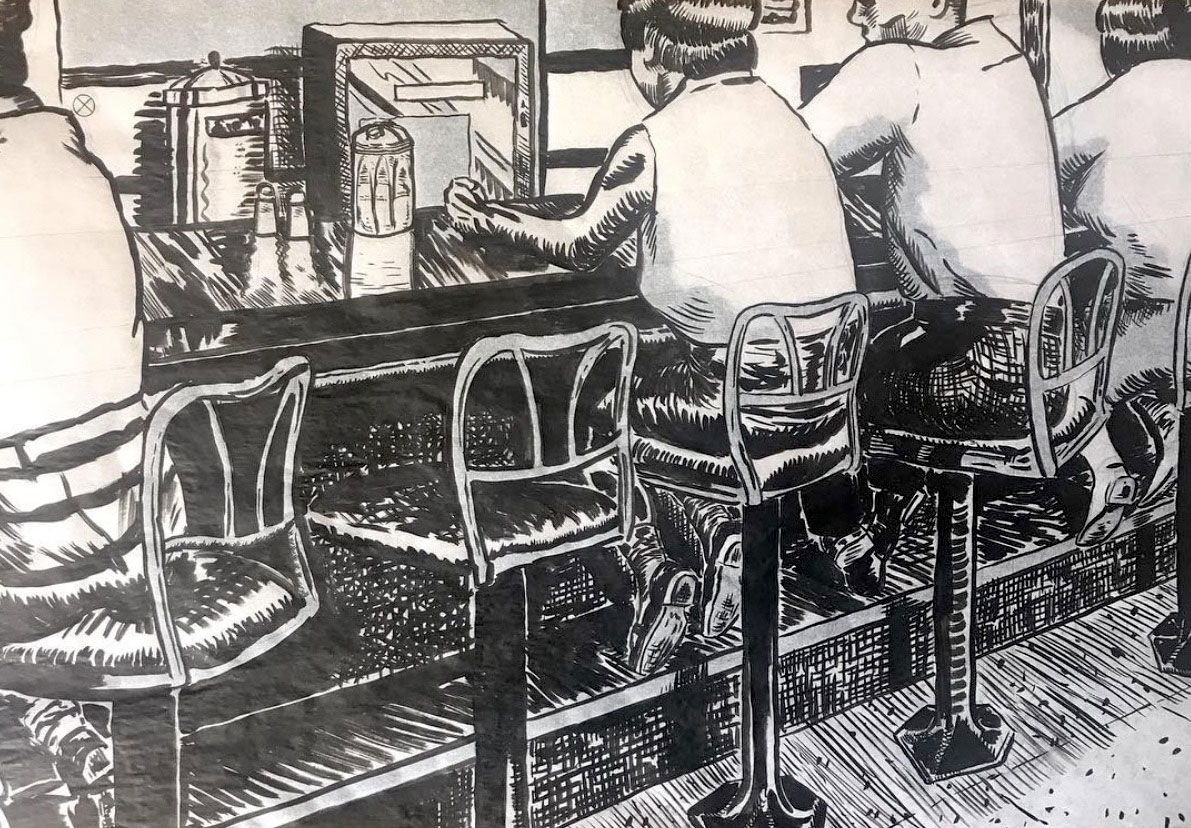

But here the thing is, people will tell you, black and white, it was never that kind of place. “

”We all thought everybody loved each other and everybody got

along, until we wanted to go sit at their counter- Lord they

went completely crazy. They wanted to kill all of us.”

—Audrey Hamilton

St. Augustine remained loyal to the Union back during Our Most Recent Misunderstanding. A slave trading center, yes, but. The early 20thcentury brought the idea of a tourist economy, and many domestic workers and laborers took jobs at the attractions: The Fountain of Youth, which is hooked up to municipal water. The “Oldest Jail,” Castillo de San Marcos, those kind of things. So that’s how it was. What’s the word? When everyone gets along as long as everyone knows their place?

Paternalism.

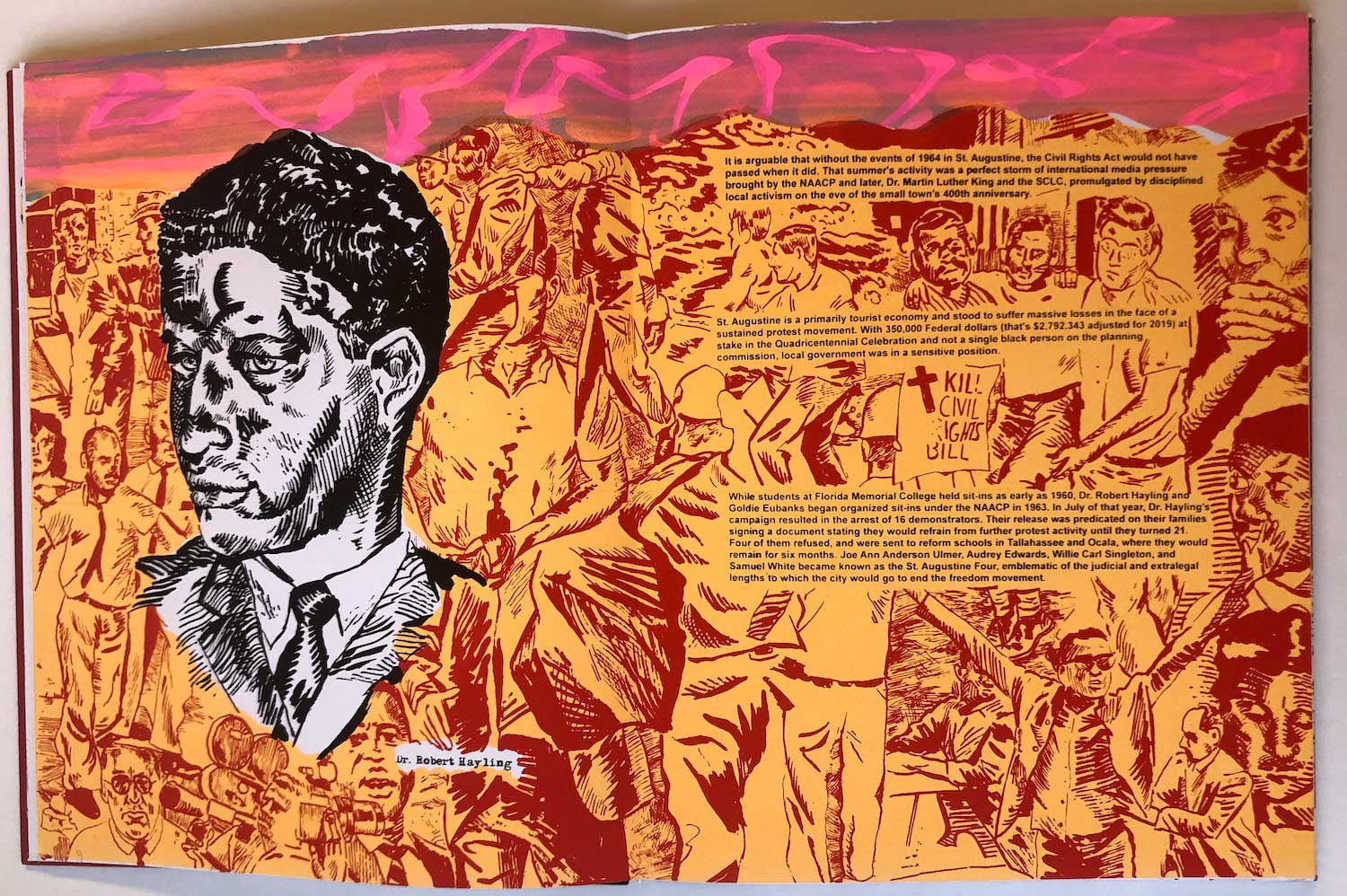

It is arguable that without the events of 1964 in St. Augustine, the Civil Rights Act would not have passed when it did. That summer’s activity was a perfect storm of international media pressure brought by the NAACP and later, Dr. Martin Luther King and the SCLC, promulgated by disciplined local activism on the eve of the small town’s 400th anniversary.

St. Augustine is a primarily tourist economy and stood to suffer massive losses in the face of a sustained protest movement. With 350,000 Federal dollars (that’s $2,792,343 adjusted for 2019) at stake in the Quadricentennial Celebration and not a single black person on the planning commission, local government was in a sensitive position.

While students at Florida Memorial College held sit-ins as early as 1960, Dr. Robert Hayling and Goldie Eubanks began organized sit-ins under the NAACP in 1963. In July of that year, Dr. Hayling’s campaign resulted in the arrest of 16 demonstrators. Their release was predicated on their families signing a document stating they would refrain from further protest activity until they turned 21. Four of them refused, and were sent to reform schools in Tallahassee and Ocala, where they would remain for six months. Joe Ann Anderson Ulmer, Audrey Edwards, Willie Carl Singleton, and Samuel White became known as the St. Augustine Four, emblematic of the judicial and extralegal lengths to which the city would go to end the freedom movement.

Once it became clear that this wasn’t going to just go away, the power structure and regional segregationist movements responded in tandem.

In July of 1963 shots were fired from a passing car at a small group of black teenagers in Dr. Hayling’s driveway. In September, Dr. Hayling and three others were seized and beaten while observing a Klan meeting outside of town. By chain and club and dumb bare fist, Hayling lost possession of eleven teeth and had both his wrists broken. But especially, as a dentist, his right wrist. The four narrowly escaped being burned alive as Sheriff L.O. Davis reportedly looked on. The four victims were charged with assault.

In October of 1963, the Lincolnville home of Rev. Goldie Eubanks, NAACP leader and high profile activist, was shot at from a passing car driven by four known Klansmen. Fire was returned by unknown parties, and one of the passengers, William Kincaid, was killed. One could imagine this being a flashpoint of sorts.

Throughout the remainder of 1963, there were several instances of gas bombs being thrown at houses in the historically black neighborhood of Lincolnville. Charles Brunson, whose child attended newly integrated Fullerwood Elementary, had his car blown up while attending a PTA meeting; the home of another Fullerwood family, the Roberson’s, was burned down by Molotov cocktails. In February of 1964, Dr. Hayling’s house was again fired into, this time narrowly missing his pregnant wife and killing the family dog. In June, the beach cottage in which Dr. King was staying was riddled with gunfire after The St. Augustine Record published its address.

The demands of the black community were fair and uncomplicated: Full integration of public businesses and facilities, representative employment by the county with opportunity for advancement, representation on the Quadricentennial Commission, and a biracial committee to explore race relations in St. Augustine.

With the arrival of Dr. Martin Luther King Jr. and the Southern Christian Leadership Conference in March of 1964, followed by throngs of Northern students to participate in demonstrations over their Spring break, the town found itself under national scrutiny. Nightly marches through Lincolnville into downtown were regularly attacked by white racists as the police looked on. Sheriff L.O. Davis deputized, among many others, Halstead “Hoss” Manucy, who had been in the car when shots were fired at Goldie Eubanks’ home. Connie Lynch and J.B. Stoner, nationally infamous Klan activists, came to town to organize the white resistance. The St. Augustine Record, very clearly making its official position known, published the names and addresses of 13 black students integrated into county schools.

The Record had also begun publishing dates for upcoming Klan rallies. United Florida KKK, Klavern 519, aka The Ancient City Hunting Club (organized by Sherriff’s Deputy Hoss Manucy) had been staging increasingly packed rallies, with as many as 2500 spectators. The Klavern was known to hold meetings at the county jail, as there was significant overlap between the Klan and the 200 new deputies; Sheriff Davis even loaned out county vehicles to visiting Klansmen.

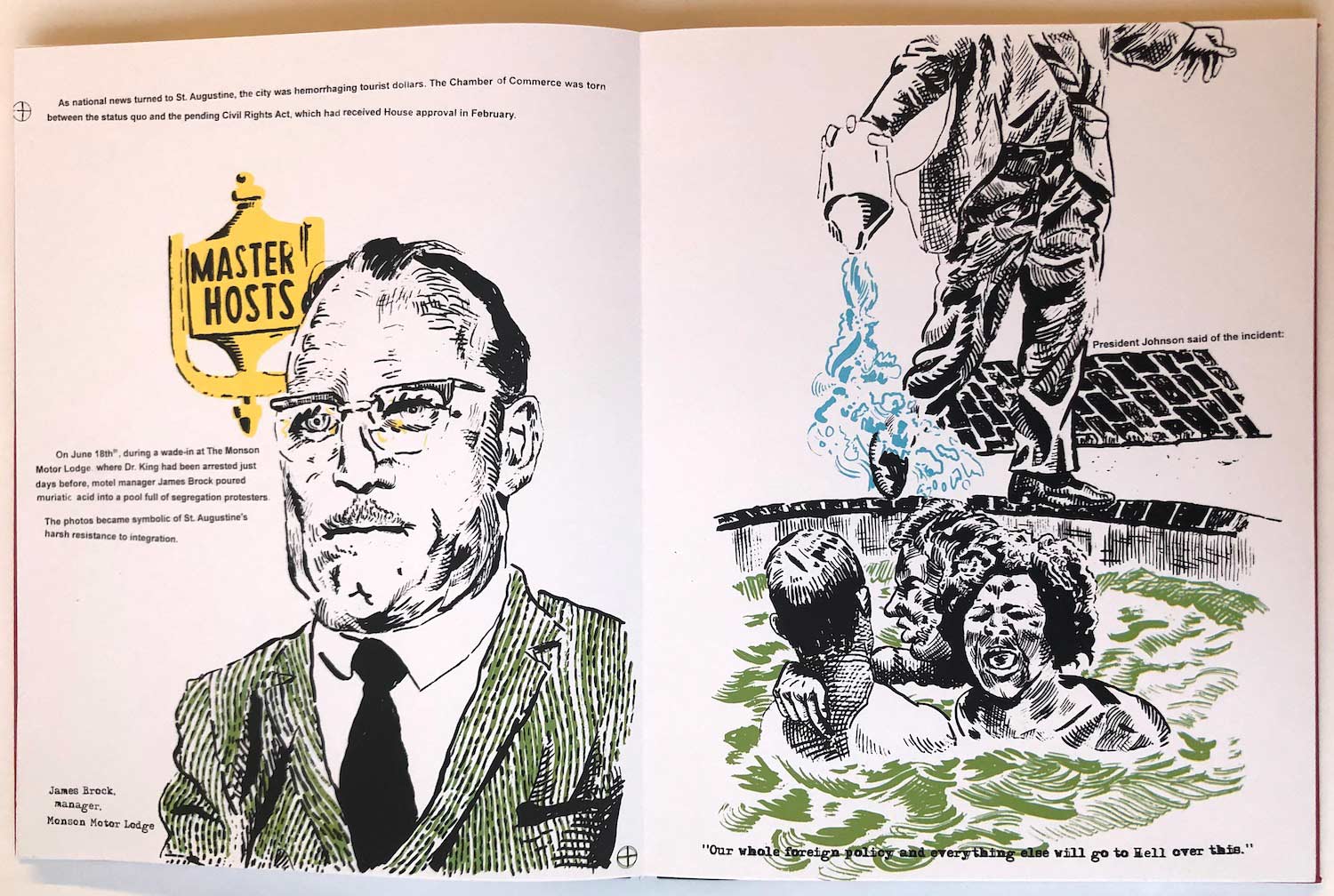

As national news turned to St. Augustine, the city was hemorrhaging tourist dollars. The Chamber of Commerce was torn between the status quo and the pending Civil Rights Act, which had received House approval in February. On June 18th, during a wade-in at The Monson Motor Lodge, where Dr. King had been arrested just days before, motel manager James Brock poured muriatic acid into a pool full of segregation protesters. The photos became symbolic of St. Augustine’s harsh resistance to integration. President Johnson said of the incident:

“Our whole foreign policy and everything else will go to Hell over this.”

Segregationists, and probably many law-abiding white folks saw St. Augustine as another domino, a metonym for the cold war, Cuba, Vietnam, and J. Edgar’s creeping stateside communism. Mayor Joseph Shelley was fighting a losing battle, but to actually establish a biracial committee to steer the future of his historical gem just seemed beyond his capacity. Even after Gov. Bryant had created a Special Police Force of 235 members comprised of six state agencies to supervise the city and county police, who had seamlessly demonstrated their allegiances with a brutal combination of negligence and participatory violence, Shelley’s official policy remained one of stubborn noncompliance with state and federal authority.

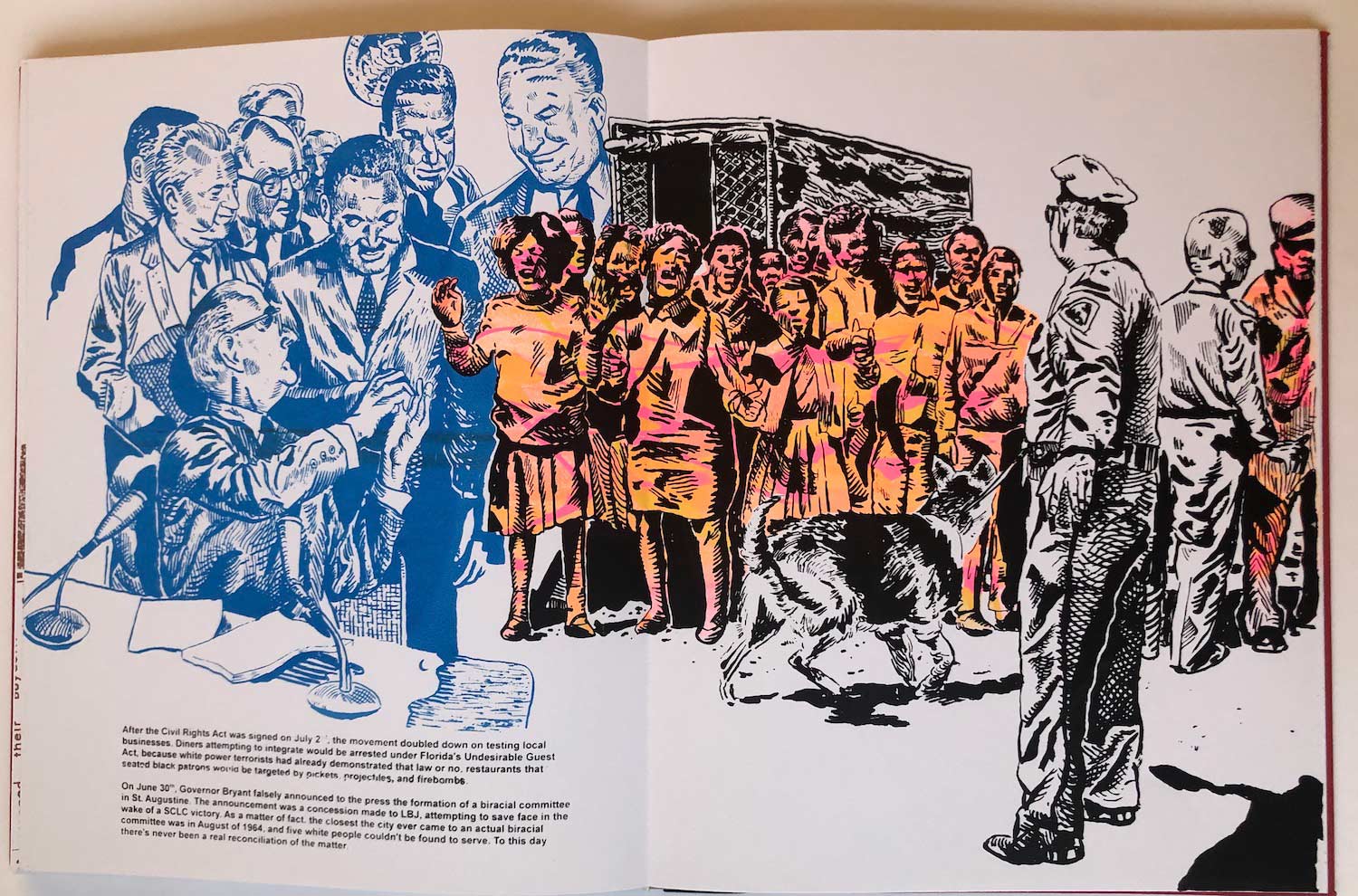

After the Civil Rights Act was signed on July 2nd, the movement doubled down on testing local businesses. Diners attempting to integrate would be arrested under Florida’s Undesirable Guest Act, because white power terrorists had already demonstrated that law or no, restaurants that seated black patrons would be targeted by pickets, projectiles, and firebombs.

On June 30th, Governor Bryant falsely announced to the press the formation of a biracial committee in St. Augustine. The announcement was a concession made to LBJ, attempting to save face in the wake of an SCLC victory. As a matter of fact, the closest the city ever came to an actual biracial committee was in August of 1964, and five white people couldn’t be found to serve. To this day there’s never been a real reconciliation of the matter.

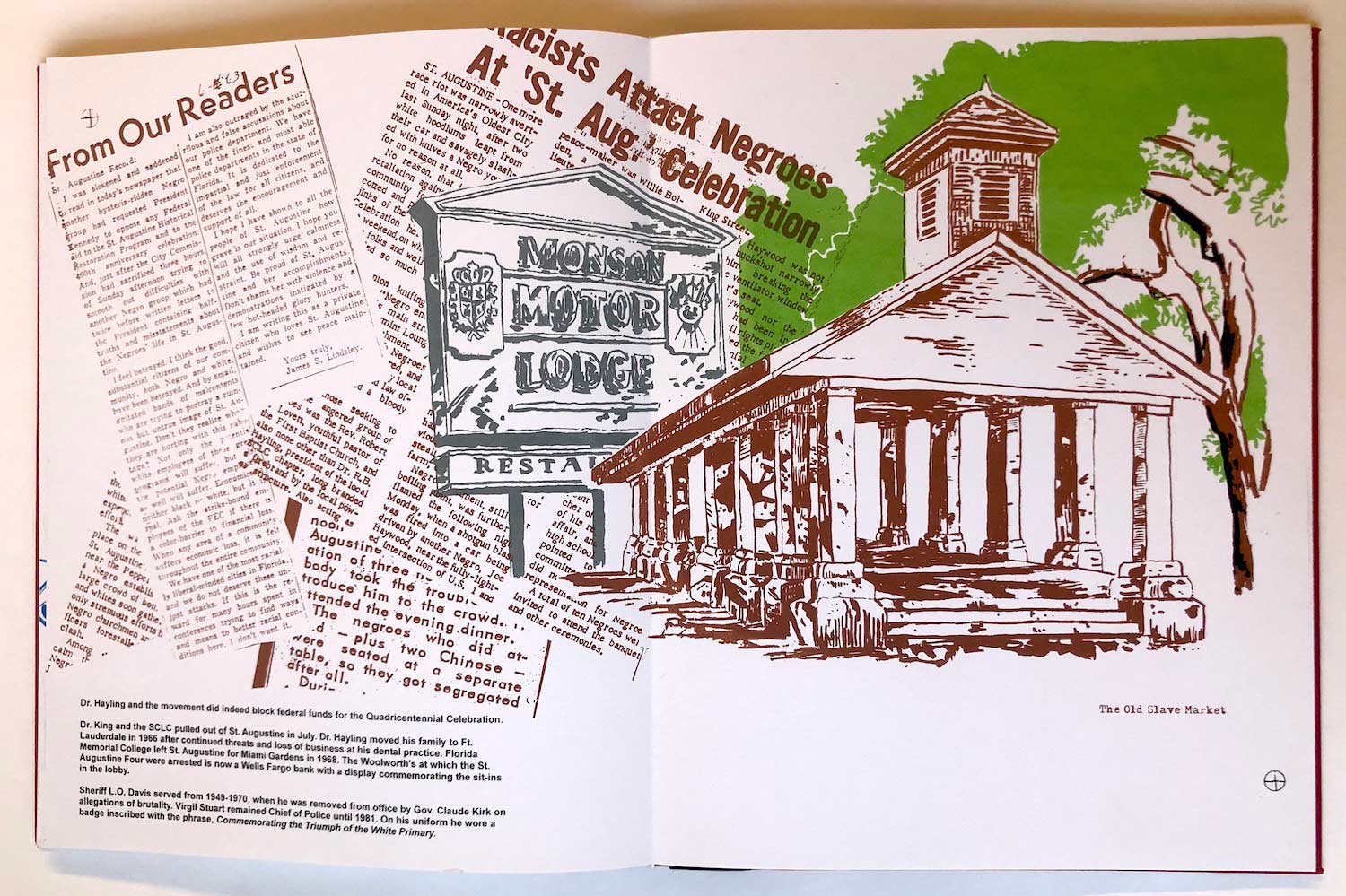

Dr. Hayling and the movement did indeed block federal funds for the Quadricentennial Celebration.

Dr. King and the SCLC pulled out of St. Augustine in July. Dr. Hayling moved his family to Ft. Lauderdale in 1966 after continued threats and loss of business at his dental practice. Florida Memorial College left St. Augustine for Miami Gardens in 1968. The Woolworth’s at which the St. Augustine Four were arrested is now a Wells Fargo Bank with a display commemorating the sit-ins in the lobby.

Sheriff L.O. Davis served from 1949-1970 when he was removed from office by Gov. Claude Kirk on allegations of brutality. Virgil Stuart remained Chief of Police until 1981. On his uniform he wore a badge inscribed with the phrase, Commemorating the Triumph of the White Primary.

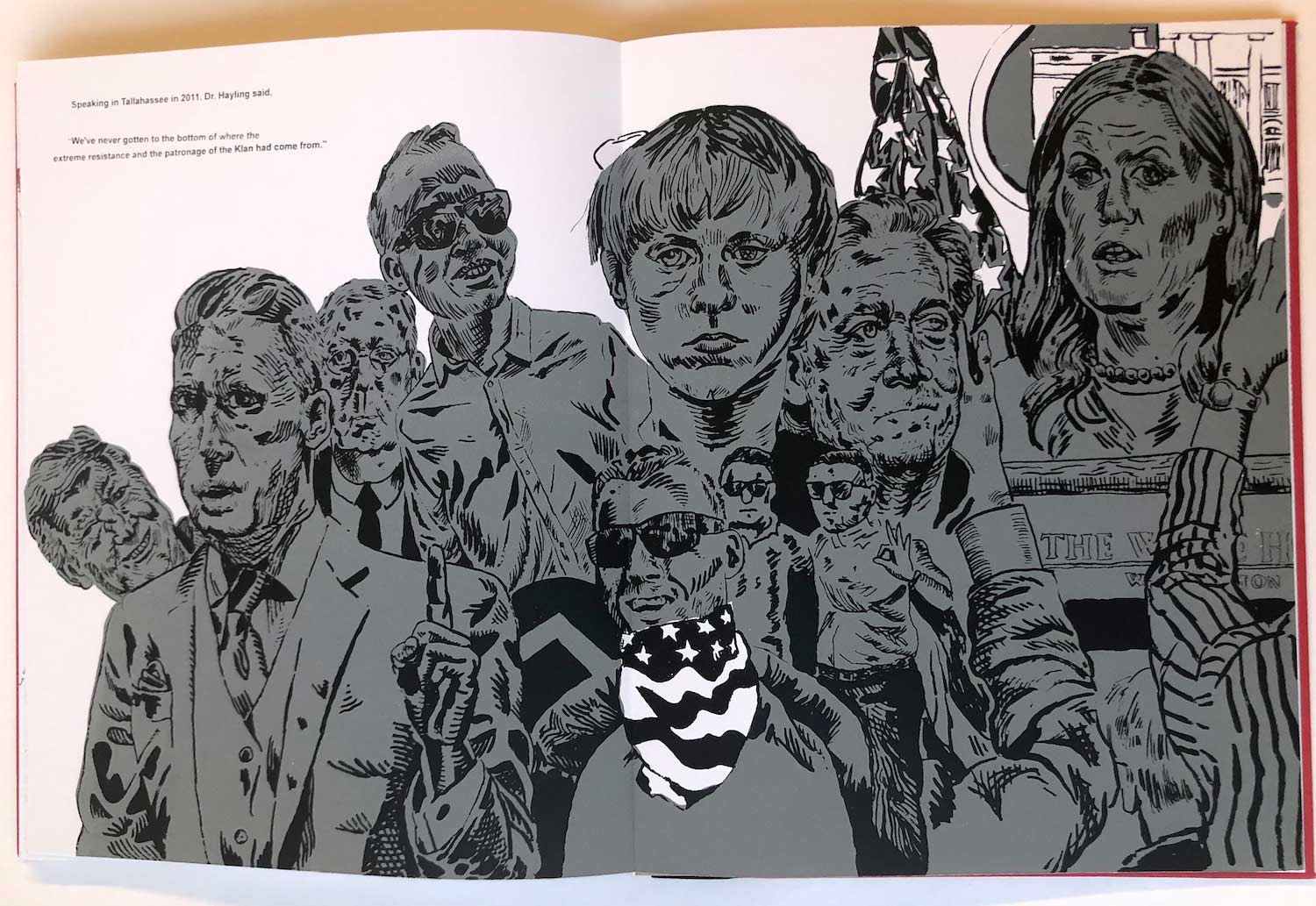

Speaking in Tallahassee in 2011, Dr. Hayling said, “We’ve never gotten to the bottom of where the extreme resistance and the patronage of the Klan had come from.”