Die Nase (The Nose)

Die Nase (The Nose)

Date

2009

Edition Size

46

Media

Letterpress

Paper

Mitsumata

Binding

Other

Format

Artist Book

Dimensions

18.9 × 13.5 in

Location

Tokyo, Japan

Collection

Collection Development, Limited Edition Artists Books$ 2,000.00

Unavailable

View Collectors

College of Saint Benedict & Saint John's University

Deutsche Nationalbibliothek

Swarthmore College

University of California, Los Angeles (UCLA), William Andrews Clark Library

Wellesley College

Württembergische Landesbibliothek

In his short story “The Nose”, published in 1916, Japanese Author Ryunosuke Akutagawa describes a vain and selfish Zen priest from the Heian era, who is agonized by his extremely long nose. Knowing that obsessions with secular things are not appropriate for his position as a Zen scholar, he suffers even more until his entire daily life is overwhelmed by his concerns about his appearance.

After different attempts, he finally finds a method to shorten his nose. At first, he is very happy with the result, but then he recognizes that everybody reacts with malice towards his new look and he wallows in self-pity that is even worse than before.

“The Nose” is one of Akutagawa’s best-known short stories and has various German translations. The text I printed is a translation by Jürgen Stalph that was written especially for this edition. When transforming this text into a book, I had two things in mind: the classical story that derives from a Japanese legend from the 13th century, the very modern theme of being unhappy with one’s appearance, and the often painful attempts to change it.

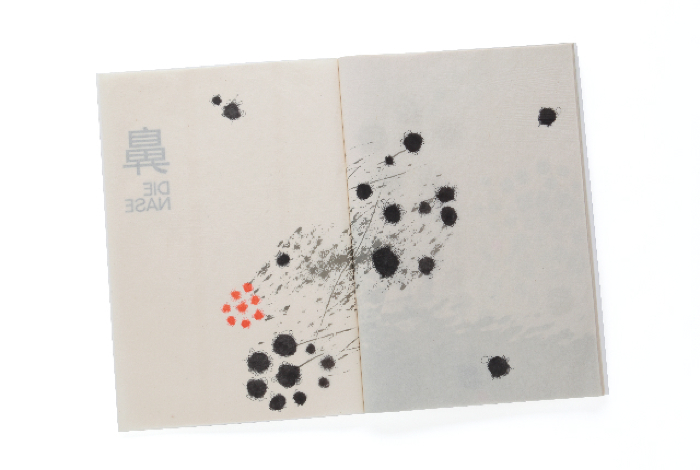

Therefore I started to collect the popular advertising material which is distributed in Tokyo at various public places such as flyers placed in taxis that promote different methods for male hair extension and hair increase, and magazines which only list beauty salons for male clients. I also read a study which focused on body aesthetics (Laura Miller, “Beauty up: exploring contemporary Japanese body aesthetics”, University of California Press, 2006) and quotes a survey on what men and women define as the established ideal of beauty. Both men and women pointed out body hair as the most unaesthetic attribute of the other gender’s body. This is only one aspect amongst many others, but it gave me the idea to work with hair in some altered form. I bought hair extensions, formed them into small balls which I then used as a model for polymer plates. Once they are printed, these round objects look at the first glimpse like small drawings rather than hair. I also made pictures of my skin, enlarged them so much that they appear only as structure.

The first and the last five double spreads show multicolored illustrations, half-transparent images composed of the hairballs and skin structures. In the middle of the book, there are six double spreads with Akutagawa’s text, the German translation followed by the Japanese original. The large-size book plays with the transparency of the paper and parts of the previous design as well as parts of the following design are integrated into the current page. The same element of composition is applied in the text, printed in small columns. Once in a while, one column is left blank and the previous or following column is shining through the paper. The thin Mitsumata paper is folded in the foredge and into each fold one thin sheet of tissue paper printed with small hairballs in pink is inserted.

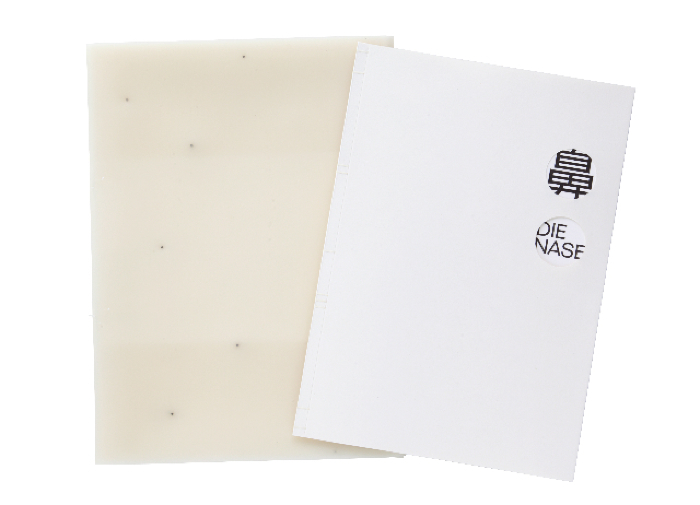

The book is bound with vellum-strips into a cover made of white Kozo-Ganpi cardboard. Two circle-shaped cutouts show the title in Japanese and German. The rear side of the cover contains three magnets fixing the book into the case.

The case is made of flexible jelly sheet whose color and feeling of the surface remind me of skin. It is folded together and closed by small Neodym magnets that are fitted into the PVC material. After one has read the whole story, the magnets might remind the reader of blackheads; the vinyl cords might remind one of the white strips of sebum which are pulled out of the priest’s nose. Because the vinyl is too flexible, I inserted a sheet of cardboard into the case, connected by vinyl cords to the jelly sheet. This cardboard also contains magnets that keep the book in its place before the cushion-like case is closed.

— Veronika Schäpers

Letterpress print from polymer plates in German and Japanese on mitsumata-paper. Illustrated with photographs of skin-structures, and small balls formed out of hair in various colors. Japanese binding with vellum-strips into a white cover of kozo-ganpi-cardboard. Case made of half-transparent Jellyfilm, vinyl cords, and Neodym-magnets. 34.5 cm x 48 cm. Edition of 40 arabic numbered copies and 6 roman numbered copies. Tokyo, 2009.