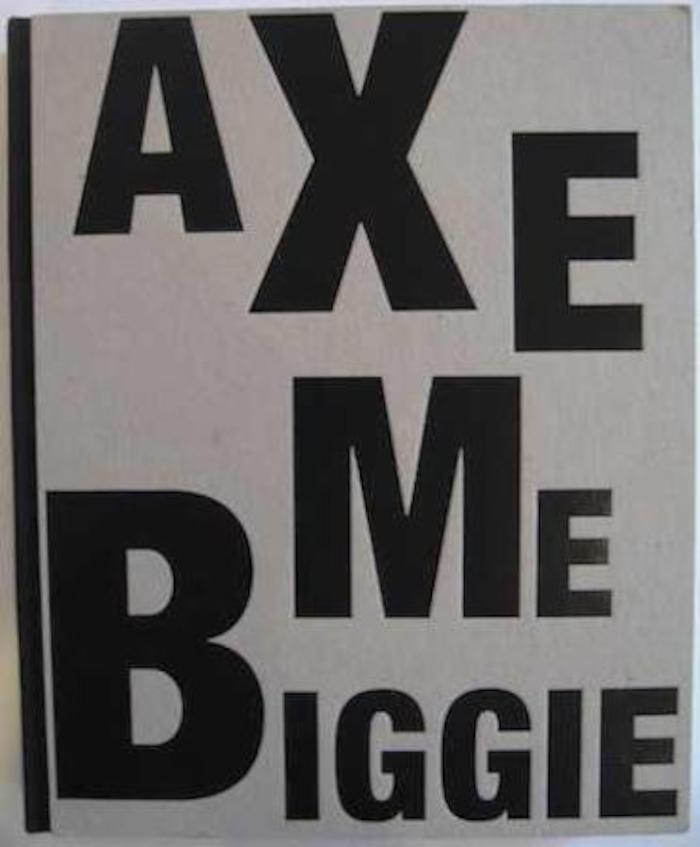

Axe Me Biggie (A.P.)

Axe Me Biggie (A.P.)

Date

2011

Edition Size

40

Media

Digital print, Photo

Binding

Hand-sewn

Format

Artist Book

Collection

Collection Development, Limited Edition Artists Books$ 3,200.00

Unavailable

View Collectors

Harvard University, Fine Arts Library

‘First the big picture, and on March 13, 2006 – the day Stephen Dupont made the ninety-three photographs in this volume – the big picture in Kabul is more bombs, more drugs, and more poor. It’s an old story by now: the foreign promise unfulfilled, the failed reforms, a country immune to money, schools, and eight-part programs, always reverting to its savage nature. It doesn’t help that Stephen and I spent the better part of the last three weeks in a mental hospital. Whatever other effects that may have had, it turned this city into a sort of violent burlesque and in my mind’s eye I see, as undoubtedly he does too, a kaleidoscopic cascade of junkies, electroshock patients, and amputees.

This volume is not about the big picture. It’s about all the small ones, the ninety-three particular, like-no-one-elses you see here. As journalists we use individuals as emblems, symbols, small faces to make big judgments. But obviously, any single Afghan, any single story, is more ambiguous, more murky than that. Take the man I met at the orthopedic hospital six hours before these images were shot. About forty years old, he was from Madianshar. I’d been there once in 2001, a kind of Wild West ghost town over which the Northern Alliance and the retreating Taliban were trading missiles. That day, listening to the whistling shells, the journalists hunkered down inside a yellow house. It might have been his, this house, the one that every night he ringed with nine landmines for protection. Every morning he dug them up again. But one morning, not thinking, he dug up only eight. The ninth he stepped on, blowing both his legs off. Imagine, he stepped on his own landmine. “We have an expression for this,” the doctor in the hospital said slyly. “He dug his hole … then he jumped into it.”

What does this story tell us? Neither nothing nor everything. And that’s the way it usually is.

Having been in many places where pictures were taken, many times I’d seen the images that emerged and didn’t recognize them. Inevitably they made the incidental appear central, manipulated light and angle to overstate drama, homed in on every spot of violence and destruction until completely erasing the less photogenic truth surrounding — and in short, had almost no relation to the scenes that I myself had witnessed.

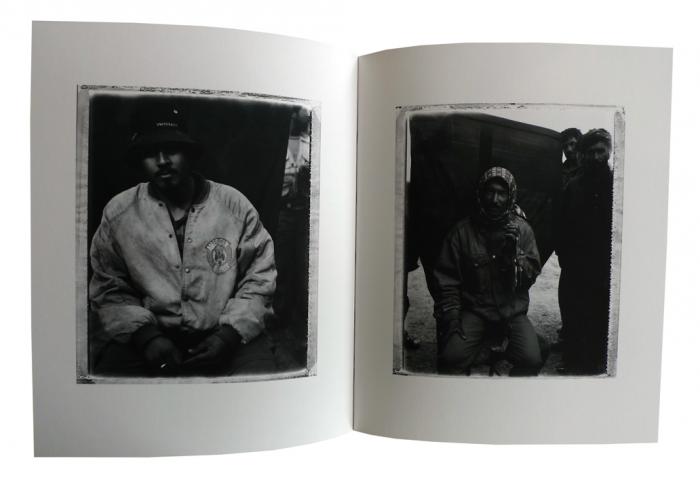

But there’s no sleight of hand here, neither from photographer or subject. It’s merely a record of how it was. The images can’t convey the carnival atmosphere we created along that dusty roadside bus stop strip with our western faces and magic Polaroids, how after ten minutes we were surrounded by a hundred people pushing and pleading to get into the chair with the attached curtain backdrop that Stephen rented from one of the local photographers, how the excitement of the crowd would grow until it inevitably climaxed with a policeman swinging a steel truncheon, chasing us farther down the road. But what they do convey, what they document, is that there is always a moment. The finger pointed, the next subject selected, the die cast, it doesn’t matter if it’s a young boy, a cop, or the man with elephantitis. He sits in the chair and as if by some secret signal the crowd goes silent and the man squares himself toward the lens. The cop checks his swing. The buses stop. The movement of the world is frozen as if anticipating its place in this book some months later, out of time, timeless.

One and all, the subjects of Stephen’s photographs seem to understand eternity and they have a certain look for it, each one, even among the blowing dust and the swelling crowds, finding this “center,” this patch of downtown Kabul magically transformed into a royal portrait studio, the rickety chair a throne on which the formal sitting takes place.

If you let it in, this sudden sensation of time arrested is a slap in the face. That’s eternity slapping you now.

A writer couldn’t do it; I couldn’t do it. And I’m sure that not a little of this is because on this day, a Monday, there is an exchange. Everyone gets a picture. Stephen is shooting 665 black and white Polaroids, one per person. After his shot, he pulls out the cartridge and separates the positive from negative. One for them, one for him. How different this is. Usually photography is a theft, or else, conversely, it is commissioned, a paid advertisement. Today it is neither; no one is told what to do. In a place where “freedom” is fast becoming a dirty word, this is a real thing. And it isn’t just talk. You get a picture to take home for nothing, so it really is “free.”

“Axe Me Biggie” — a crude Anglo phonetic rendering of the Dari for “Mister, take my picture!” — is Stephen’s answer to the plea he’s heard all over town the previous three weeks. It seems to mean something in English, “axe” being just a more visceral and violent version of the camera verb “to shoot,” returning all its original aura of surrender. And because Stephen has that pulverizing Aussie-rules rugby body, “Axe Me Biggie” also seems a request addressed to him personally. Stephen is Biggie. And on this day Biggie finally answers them all, en masse, saying, “Yes, alright. I will axe you, shoot you, take your bloody picture. Have a seat!”

Here, speed acts as the slayer of editorialization … of bullshit. The entire session unfolds over a cluster of locations within two hundred yards of each other, unfolds in three hours, between three and six PM, or roughly one picture every two minutes. Now ordinarily we prefer our art to be long suffered over, if only to feel we’ve gotten our money’s worth. This is the opposite. And it gives all the benefits of the opposite: no time to fuck around, to prevaricate. The photographer, as he should, becomes irrelevant. Only that moment, that eternal moment that the Polaroid Land Camera creates, tearing a space in the continuum of time.

In the gap, these faces. The faces ninety-three Afghans present to you, and to themselves. They confound, rejecting every attempt to be tidily stored away in the mental filing cabinet, and yet strike that deep-timbered tone: recognition. It says, I don’t know that man; I know that man. I don’t know that place; I know that place. I know, in that soul way of knowing birth and death, that look … when I am, you are, he is, staring life in the eye and in the tripping shutter of the camera life blinks first.’

Jacques Menasche

New York August 2006